Part 1: Strange Child

Between around 1987 and 1992, when I was between the ages of about nine and fourteen, the video shop was a place of wonder. I must have spent hundreds of hours wandering around looking at the box art, particularly the spray-painted schlock of the sci-fi and horror genres. And because my parents copied these tapes after renting them, we accumulated a large library from which I borrowed once they’d went to bed. These included all the 80s classics such as Videodrome and Hellraiser, as well as an abundance of b-movies, big-budget flops like Krull and Dune, and straight-to-video trash.

Inspired, I make up my own stories and enacted them with my toys in sometimes blatant homages to movies I’d recently seen, or simply made up based what I imagined from the cover. I’d remix elements and concoct my own epic space operas and demonic nightmares. The toys I used ranged from big late 80s brands such as Mask, Starcom, and Transformers (laterally, GI Joe), little rubber finger monsters, and sets made of board games, bits of perfume bottles, bike reflectors and whatever else I could get my hands on.

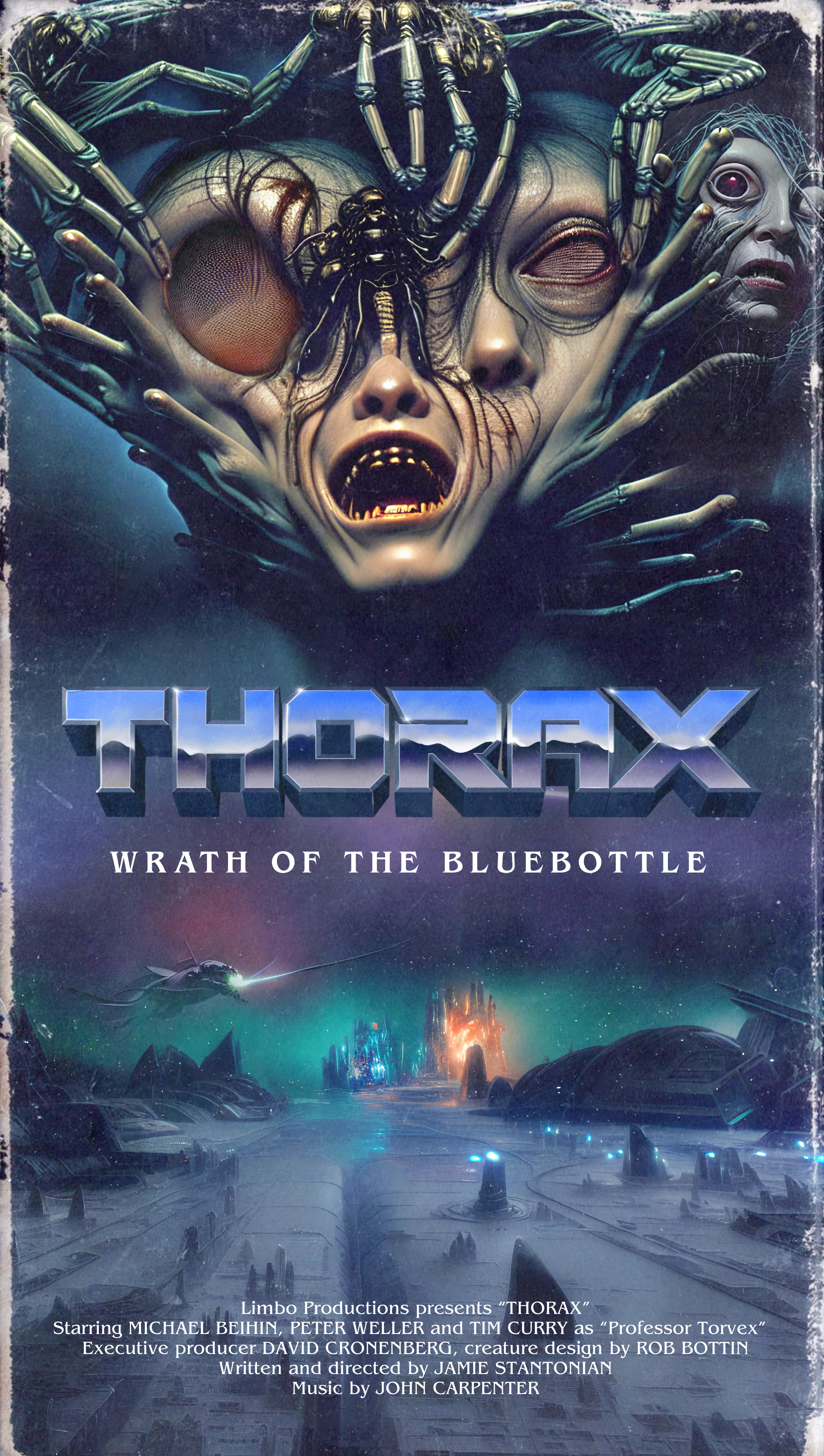

Once I’d played through the story a few times and nailed the plot and key scenes, I’d draw pictures of the them and importantly, the VHS cover art that accompanied it, a hobby that continued for many years and resulted in a large archive of notes, plotlines, and “concept art”. A personal favourite of these stories was a synthesis of various popular sci-fi/action/horror movies a the time. Set on the icy world of Pluto, Thorax was about a team of scientists hunted by a horrifying shapeshifting Bluebottle that can both imitate and absorb humans (a-la The Thing, The Blob) and mutate and multiply into a grotesque horde of insect warriors (Aliens, The Fly). Packed with sci-fi horror and spectacular action set-pieces, it was an adolescent ayahuasca trip across the 80s media environment.

It ripped-off and fused together so many things that it made something almost new in the process; a space opera spanning seven movies and multiple centuries, and genres from backstreet horror to interplanetary war. The story became the basis of my very first piece of digital art, which by extraordinary luck was caught on camera in 1990 the day after I received an Amiga 500+ for Christmas. Rather than 12-year-old me drawing an insect, I drew a giant eyeball, probably because it was easier to make in Deluxe Paint II.

Part 2: “Make New Creature for Thorax”

One of the last pictures I made in the Thorax “series” in around 1992 offered a challenge; “Make a new creature for Thorax”, accompanied by a slightly more technically proficient but lifeless drawing. And now, 30 years later, I decided to take myself up on the challenge again, aided this time by the power of Generative AI, primarily Stable Diffusion. I’d been looking for an excuse to dabble in the strange, exciting, and controversial family of technologies for a while, and what better reason that to try and soft-reboot my own imagination.

Step 1: Generic generations

I began with prompts like “grotesque shape-shifting fly turning into human” applied to things like the cover of David Carradine’s “Crime Zone”, hoping naively that the AI would somehow absorb the aesthetic and neatly fuse it with the prompt. And while some of the outputs were visually impressive (sometimes veering on the disturbingly erotic) they didn’t match the schlocky, pulp vibe I was aiming at, and no amount of prompt-crafting seemed to really get close to the layout either.

Step 2: BASE IMAGE Composition

A crude layout for a source image, made in ProCreate.

I wanted as best I could to replicate the overall layout of the original Thorax “cover”; the monster’s head looming over its prey from cosmic night. To this end, I decided to throw together a very crude composite picture made out of random google image searches, shown here in its copyright-infringing glory, watermarks and all.

At its very start, it threw into question the morals of using the art of others as a source. But how much of the original would remain once digested in the bowels of Stable Diffusion? Would it even be recognisable? Here we head into the murky no-mans-land between influence and theft.

Step 3: Experimentation

After uploading to PlaygroundAI, I spent some time fine-tuning the image strength and quality of the input image, and experimented with a variety of prompts, including detailed descriptions, outlines and artist names. A sort of aesthetic search engine.

Brilliant 8k portraiture feature, body horror, monstrous insect fly human face over an exploding futuristic city on an icy waste

Not exactly Ovid, but enough to dredge from the depths of the algorithm some approximation of what was in your minds eye However prompts like these seemed to get confused when balancing the different conceptual elements in a visual form, so I decided to split prompts between the three main ones; the icy waste, the horrifying creature and the futuristic city. With the same composition and color palette, I decided I’d then merge them back together in Procreate to achieve the look I wanted.

I must have generated thousands of images, some spectacular, some interesting, many just plain bad. In this sense Generative AI is like the infinite monkeys on infinite typewriters, endlessly rattling out new creations based on random seeds until you intervene and tell it they’ve created Shakespeare (Or in this case, bootleg David Cronenberg).

Step 4: Re-Composition

Once I felt I’d generated enough of each element to a sufficient quality, I layered them in ProCreate and began creating a composite image. This posed some new creative choices. The original cover depicted a small research outpost based on the Starcom Starbase Command playset (1986), but Stable Diffusion had expanded this into a sprawling metropolis which expanded the canvas of the story. The monster itself strayed far from the adolescent depiction of a rubber fly, and deeper into the meaty surrealism of Cronenberg and Carpenter.

Step 5: The Back Cover

Given these stories were initially told with Coleco’s Starcom toys, it felt fitting to use snapshots from box art and cells from the animated show as source images to riff off. Like the front cover, I layered and blended the images until I got a good balance of all the visual storytelling elements. Looking towards the star-spanning grandeur of the coming sequels, I began to generate images of enormous battles between Pluto’s military forces and the insect swarm. Images so strange that they unveiled new ways of reimagining the story, exploring worldbuilding and again conjour prompt ideas to feed to the AI.

Brian Eno once said that

“Whatever you now find weird, ugly, uncomfortable and nasty about a new medium will surely become its signature. CD distortion, the jitteriness of digital video, the crap sound of 8-bit - all of these will be cherished and emulated as soon as they can be avoided. It’s the sound of failure: so much modern art is the sound of things going out of control, of a medium pushing to its limits and breaking apart..”

One thing that generative AI does wrong - as critics complain - is drawing faces and hands. And the closer it gets to photorealism the more disturbing the errors become. Having always had a love of body-horror this is something I delight in, and have spent hours generating glitches on This Person Does Not Exist like a boomer on a slot machine. Perhaps because they are rare, they are like catching a glimpse of something from the side of your eye, or the edge of imagination.

I wanted to use these shortcoming to my advantage to help depict the more gruesome elements of the story. Using a photo from Unsplash as a source, I rattled in prompts based on basic descriptions (man transforming into fly) alongside the names of movie directors and artists, but many of the initial batch were just a little too slick, so I chanced it by adding “creature design by Rob Bottin” . Bottin is regarded as the Michaelangelo of gory SFX in the 1980s, and I was curious as to what effect this would have on the look of the image. Turns out quite a bit, suitably mimicking the cinematic quality of the medium and glistening exposed flesh of the monster.

Step 6: The Finished Cover

After laying out together the front and back, I painted the chrome title in ProCreate and tracked down a suitable texture to map over the top to add that delicious distressed look. Overall, I’m pretty happy with the outcome, although I do wonder if I could have wrangled it to be more closely aligned to the original, as it perhaps still looks a little too modern in places. However it was a great exercise to try and explore the boundaries and limits of generative IA and I look forward to exploring the covers of the six sequels.